The abuse of a child is an offense that many citizens will agree rises to the level of unacceptable in the eyes of society. When we break down what truly is child abuse and what isn’t though, the lines blur – strangers tend to avert their eyes to family issues that don’t concern them when it’s shrouded in the ambiguity of punishment and discipline. As someone who isn’t involved in an investigative professional role, it’s also hard to know not only what rises to the level of abuse, but also – what is done about it?

Each day more and more information is available to us at our fingertips through social media outlets. When mindlessly scrolling at the end of our day, the last thing we expect to see is a post or news article about a child being hurt in our own community, being abused by the caregivers who are supposed to be the people keeping them safe, or a trusted member of the community. What you don’t see behind that news article is that that one story is one of hundreds in your own backyard. Something egregious about that abuse caught the attention of the media, yet every day a child is abused or neglected every 47 seconds in the United States[1]. It’s natural to feel angry or sad when you hear about a child enduring physical or sexual abuse, and shrouded in the anonymity of the internet it is even easier to voice opinions about what should be done – but what is being done? How is the system protecting children and holding offenders accountable?

Let’s Walk Through It.

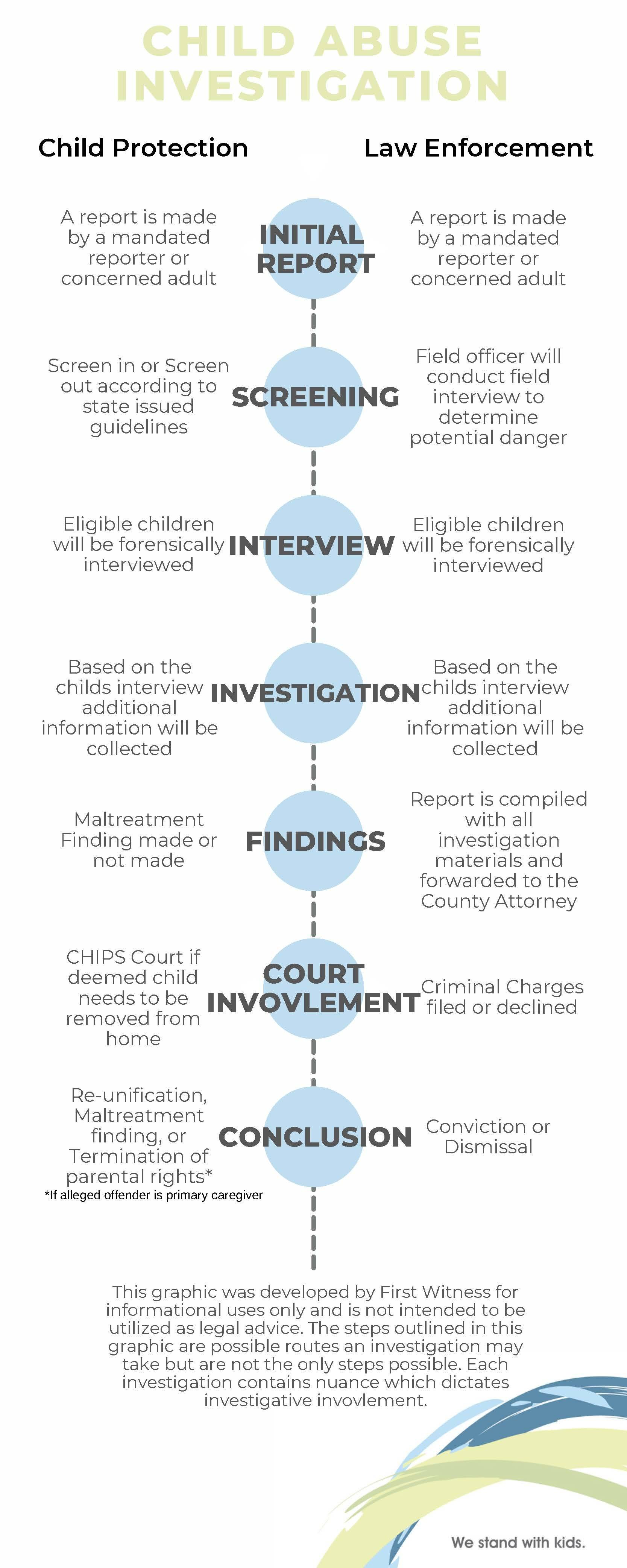

Step One: Report

An adult either witnesses an incident of possible abuse, has suspicions or concerns of the possibility of abuse, or a child makes a direct disclosure about abuse they have endured. That adult does not need to be a mandated reporter to make a report to either County Child Protection or the Law Enforcement jurisdiction in which the possible abuse occurred. For more information on making a report, check out this article by one of First Witness’ Family Advocates, Ryan Prouty: Recognize, Respond, Report: How to Make a Report of Suspected Child Abuse if I am Not a Mandated Reporter.

Suspected abuse or maltreatment should always be reported, even if you feel like you don’t have proof. As an adult caring about the wellbeing of your child, it isn’t your responsibility to find or have the proof – that is someone else’s entire professional job description. Leave the investigation to the investigators. Depending on the nature of the alleged abuse and the agency it was reported to the outcome can look slightly different, so let’s break that down too. From this point forward, two independent investigations about the same incident will happen alongside each other. Each of those two separate investigations could come to completely different outcomes.

Child Protective Services Response

County Child Protection agencies follow a screening protocol to document, assess, and assign reports of suspected child abuse and maltreatment. When making a call to a county service, a screener will take down all the information you are able to provide and then it will be assessed to determine if it meets the standards set by the state of maltreatment or abuse. If the information provided does NOT meet those standards, then the report is “screened out” which means that the investigations team will not be opening a child protection case, but some agencies will forward the information to voluntarily family assessment services to help. If the reported abuse or maltreatment does meet the standards, it is “screened in” and assigned to an Initial Intervention Unit Social Worker (some agencies call this Initial Assessment Social Workers, or other similar job titles). If a report is screened in and assigned, an investigation will start to determine if the report is valid and if the child is in danger. Reports are forwarded to the local Law Enforcement jurisdiction to cross report the information.

The State of Minnesota’s Department of Health and Human Services publishes their screening guidelines and every county in Minnesota is held to the standard set by that document when assessing and assigning reports of child abuse or maltreatment[2].

Law Enforcement Response

Law Enforcement agencies take initial reports from concerned parties and from there several initial responses can happen. These responses may include but are not limited to:

- Depending on the level of severity of the alleged maltreatment or abuse, if it is believed that the child is in immediate danger, a patrol officer may be dispatched for a welfare check.

- If the report came from social services as a cross report, they will discuss a coordinated initial response.

- An investigator will be forwarded the report information and they may consult with other agencies such as the County Attorney’s Office to determine the appropriate level of involvement.

- An investigation will start.

Step Two: The Investigation

Forensic Interview

Southern Saint Louis County and Carlton County have established a Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) alongside First Witness to respond to child abuse. What that means is that any agency that could potentially be involved in a child abuse investigation all work together to provide a coordinated response. Child Advocacy Centers, such as First Witness, are the epicenter of that MDT, bringing all of the appropriate agencies to one table to provide the most appropriate responses to a child and their families instead of, historically, when families would have to go to each individual agency and repeat their story – possibly revictimizing the children involved in the process.

Remember, from the report moving forward, County Child Protection Services and Law Enforcement conduct separate investigations; the MDT allows both investigations to gather direct information from the child and family in one encounter utilizing Child Advocacy Centers. The first step in the investigation will likely be for the investigation team to reach out to First Witness and schedule a forensic interview – a neutral fact-finding interview that is conducted by a highly trained forensic interviewer. At First Witness, we utilize a protocol developed and housed by the Zero Abuse Project, the ChildFirst® protocol[3]. This protocol was developed and is utilized because it is nonsuggestive, nonleading, and very intentionally child led. What does that mean? It means if a child is identified as a potential victim, we want to hear their words – allowing that child to feel safe and supported in a child friendly space when talking to a neutral person who isn’t involved in the investigation. Those words are given to the investigators that need it, without exposing the child to a potentially stressful or coercive interaction. These interviews are forensically sound – that means that if a child’s disclosure led to criminal charges, this interview is evidence that can be utilized in those proceedings.

Corroboration

After a child is forensically interviewed it is common that Law Enforcement and Child Protective Services will continue to work alongside each other in gathering corroborating findings. What this means is that they need additional voices, images, or evidence to support a child’s story. Unfortunately, we live in a society that doesn’t consider children credible – so, to ensure that findings can be substantiated or proven without a doubt in the criminal justice system, the investigators assigned to the cases need to do their due diligence to obtain as much corroboration as possible. This often looks like speaking to other people that the child named in their interview as witnesses and exploring the alleged location of abuse to document that it looks the way the child described. When an alleged offender is named by anyone in a violent offense, that person has a constitutional right to be interviewed as well – they have the right to decline, as many do, but that interview would also be used as corroboration. This step is especially important if the alleged abuse rises to the level of potential criminal charges – with every case that could potentially produce criminal charges they need to have more than enough information to prove to up to twelve strangers that the child is telling the truth. Remember, you or I may think everyone should believe every child if they are saying they are being abused, but that isn’t the case. Society deems a certain level of potential abuse as acceptable, or within the family – and as adults believing that a child misunderstood an event is more palatable than accepting that abuse happened at all.

Family Involvement

The criminal justice system, child protection, and the investigation process inherently has gaps – the goal is to ‘catch the bad guy’, it isn’t necessarily to ensure healing for a victim. Due to those gaps, advocacy programs such as that at First Witness pairs families with advocates to help them navigate those gaps and ensure that systems work for families, not the other way around. When multiple systems become involved in a family’s life because of a disclosure, the effect can be overwhelming. It is important to understand that if a child alleges abuse, the potential system involvement for that child and their family goes well beyond one law enforcement officer and one social worker, it could also include additional systems such as:

- Mental Health Professionals (Therapists, Admin, Insurance)

- Medical Staff (Doctors, Nurses, Admin, Insurance)

- County Services (Ongoing Case Management, Family Services, Foster, Guardian ad Litem, etc.)

- Law Enforcement (Initial Responder, 911 Operator, Investigator)

- County Attorney (Prosecution, Judges, Clerks, Defense Attorneys, Victim Witness Advocates)

- Forensic Interviewer

- Additional Advocacy

- School/Religious Institutions (Attendance, Teachers, Counselors, Clergy)

Answering to all these different agencies and systems can be overwhelming and can lead to several risks and coping strategies that could look ‘unhelpful’ to outside perspectives. Understanding that everyone deals with trauma differently and cope differently is important for investigators to know. Advocates help to bridge this gap in communication between families and systems to provide clear communication and understanding.

Step Three: Findings and Conclusion

Reports

When an investigation is concluded, the two investigative agencies will both come to their own independent conclusions. All information gathered during the investigation will be compiled into comprehensive reports from each agency. Below are options for how each agency may proceed post-investigation.

Child Protection

Based on the information received during the investigation, the Child Protection team will determine if the child is indeed in danger or not – this is often referred to as substantiated or unsubstantiated. Unsubstantiated does not mean that the social worker does not believe abuse occurred or does believe, it simply means that according to the report, they are not able to absolutely prove that it did occur while substantiated means that they can. If a report is substantiated, they will often file a maltreatment finding against the offender. This is different from criminal charges, is not available to the public, but will remain on Human Services reports and could potentially disqualify someone from several professional positions working with children or vulnerable adults. Alternately, if the abuse is substantiated against the child’s direct caregiver(s), it will be forwarded to CHIPS (Child in Need of Protection) court. This is where a judge will determine if it is necessary to remove a child from their caregivers either temporarily (first choice) or permanently (termination of parental rights).

Law Enforcement

Unlike the Child Protection system, Law Enforcement does not make determinations on the outcome of what they gathered during the investigation. The Law Enforcement investigator compiles all the collected information and evidence in a large report and that report gets forwarded to the County Attorney’s Office. At that point, one of three options can happen. The prosecuting attorney will review the information and decide if the alleged crime fits existing criminal statutes and if the investigator was able to gain enough information that the prosecutor would be able to prove without any doubt that the crime in fact happened. After reviewing the information, the prosecuting attorney will decline charges, pursue charges, or ask the investigator to go back and gather additional information before making that decision.

Criminal Justice

Once an investigation is concluded all the deciding power is held by the County Attorney’s Office. County attorneys (prosecuting attorneys) are elected officials, but often rely heavily on assistant attorneys in larger counties. It is their job as the prosecuting party to ensure that the alleged crime fits into the existing statutes that outline what constitutes a crime, and that they can prove in open court that the event happened without a reasonable doubt. The latter is the reason that child abuse crimes often go unprosecuted. Child abuse crimes happen behind closed doors in secrecy. That leaves a lot of space open for a defense team to pick apart a child’s disclosure when there is little or no evidence to support their words. It’s also important to know that if a prosecutor plans to pursue charges, the criminal justice system is not victim friendly, and it’s a very long and drawn-out process. It’s common for years to pass before a criminal conclusion is found – especially now due to complications brought on by the Covid-19 Pandemic.

So, Why Aren’t They Arrested Yet?

When someone commits a crime, like theft, the investigation has a lot to work with, such as video surveillance, eyewitness testimony, and physical evidence, such as fingerprints or the stolen items. It’s usually a fairly concise process to narrow down suspects and more cut-and-dry when considering how a jury would act if things moved to a jury trial in criminal court. Taking this same idea into account, consider child abuse cases. We know through empirical research that children often keep abuse secret for 2-3 years before feeling safe enough to disclose. We also know that those abusers are tactful, manipulative, and careful. Criminal cases regarding child abuse all come down to one child’s words. That’s a lot of pressure to place on a child that has likely already endured years of trauma – yet that is how the criminal justice system must operate to uphold Americans’ constitutional right, “innocent until proven guilty in the court of law” and unless that child gives a near perfect account of the abuse with corroborating evidence, it’s an uphill battle for conviction. Alleged offenders are just that, alleged and therefore not likely to be arrested.

To most, this information is unsettling. As humans, we want to seek justice for the innocent – but what does that mean? If the system is set up in such a way that children are being re-victimized in that pursuit of justice, what does it do to those children to see the information about their disclosure shared virally among Facebook pages and Instagram? What does it do to a child to know that their peers are now learning about their private abuse? The system isn’t perfect, it is far from it, but taking matters into our own hands as citizens is far more dangerous for the children who have experienced the worst already.

References

[1] Child abuse statistics. (n.d.). Children’s Advocacy Centers of Tennessee. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from http://www.cactn.org/child-abuse-information/statistics#:%7E:text=A%20child%20is%20abused%20or,abused%20in%20the%20U.S%20annually.

[2] Minnesota Department of Human Services. (2021). Minnesota child maltreatment intake, screening, and response path guidelines. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-5144-ENG.

[3] Zero Abuse Project. (2022). ChildFirst® forensic interview training. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.zeroabuseproject.org/for-professionals/childfirst-forensic-interview-training/